Classical Liberalism or Post-Liberalism?

Both are wrong, dialectic is a bitch, and it's the Reformation, stupid

We live in times of chaos, degradation of culture and society, and a profound loss of faith in our institutions.

In response, two camps have emerged with very different propositions about how to get out of this mess: 1) those who blame our woes on the treason of our classically liberal principles, such as a focus on individuals and their rights, impartial secularism, rationality, and what is often referred to as Enlightenment values, and 2) those who see such liberal ideas as the root of our problems: the whole liberal project, to their minds, already contains the seeds of its own destruction, and was a bad idea to boot.1

One camp seeks a return to classical liberalism; the other seeks to ditch liberalism, possibly returning to pre-liberal ideas.

Both camps, I would suggest, miss the mark for the same reason: they are in the thralls of ideological abstract thinking. What we need instead is to embrace historical thinking.

Abstract reasoning seeks to eliminate history and context, and treats political and philosophical ideas as timeless answers to eternal questions. Whether feudalism is good or bad, or capitalism, or individualism, or secularism, or even specific policies such as nationalization or privatization, the degree of religious freedom for groups and individuals, or the form and degree of democracy, from the abstract-timeless perspective, can be answered a priori: if we think hard enough about it, the best, universally true answer will emerge. Capitalism, feudalism, privatization, or whatever, is better a priori, period.

In contrast, historical thinking sees all such issues in their historical context. Political and philosophical ideas are not timeless truths or falsehoods, but attempts to answer specific questions and tackle specific challenges emerging at specific times.2

What’s more, historical thinking recognizes that the idea of us being detached from our past, and that we can therefore freely operate in the realm of abstract ideas and impose our solution on society, is dangerously misguided. Again, the error here is overabstraction: the pretense that ideas are timeless, unrooted, removed from the organic, intertwined, dialectical, flowing nature of history and our existence in it.3

From this perspective, neither a doubling down on classical liberalism, nor an abolishment of liberalism make any sense. Both positions are delusional: they can’t happen; they are opposed to reality.

Classical liberalism was an answer to historical circumstances that were very different from our own. We may be inspired by it and still see wisdom in some of these ideas, but they are not universally true or universally applicable. We live in a very different world now.

You can see this tension in the sparks flying around discussions of free speech in a globalized high-tech world of hyper-connected social media bubbles; in the attempts to ban political parties or candidates in the name of “democracy” when society has lost its shared assumptions, its founding myths. In the debates about laïcité when there is no Christianity to be managed, much less different denominations at each other's throats, and no minorities to be protected from the mainstream religion: for there is no mainstream religion anymore. In the debates around “color blindness” vs. race essentialism in a world of racial tensions that hadn’t existed in Europe when liberalism was born. And so on.

We can, and indeed absolutely should, look to the past, recognize our roots, and see ourselves as part of a long tradition, including a strong tradition of liberalism. We shouldn’t, and can’t, however, pretend that some abstract ideology from the past is timeless, and that we can just go back to it: liberalism has had its run for the money, but such ideas always have, always will, eventually morph into something new: something that will answer the questions of our time.

Notice that I used the word “morph,” as opposed to “overthrow” or “replace.” We can never radically cut out entrenched ideas, including liberalism, or pretend they never happened. It is impossible, and the attempt therefore just as disastrous as trying to walk through a concrete wall. Which brings me to the error of the other camp, the post-liberal princedom of the RETVRN crowd.

Those who seek a return to a pre-liberal world, too, ignore our historical existence, our being in time. We can’t help but think along the lines of our current historical-intellectual trajectory; and liberalism is a strong, even dominant part of our heritage, like it or not. It will continue to shape our thinking and our world for a long time to come. Pretending otherwise is to deny reality.

Such counter-revolutionary ideas are even counterproductive from the perspective of those who pursue them. Just like Adorno and Horkheimer, by railing against what they took to be the Enlightenment, in fact reinforced the liberal reading of history—i.e. the Enlightenment Myth—, so will railing against liberalism reaffirm its project, its values, its historical narrative. Dialectic is a bitch.

Even if we somehow managed to get rid of liberalism politically, it would persist in our collective memory, in our mores, in the way we think and act. It will be “encapsulated” and can “break out” again.4 Indeed, the very fact that people today are talking about neo-feudalism and a new nobility attests to that: centuries of liberalism, capitalism and post-modernism couldn’t get rid of these ideas; in a sense, they helped preserve them, reinforce them, drench them in attractive light.

Even on the more visible level, we still have kings and queens. European nobility is alive, if not exactly well. (Just secure an invitation to a hunt with these guys and see for yourself.) In America, not long was the revolution over did elites get busy recreating the British aristocracy, minus the titles. Postmodernism has mated with the Enlightenment zombie to birth Steven Pinker (there’s a thought); Nazism has shaped globalized human-rights-neo-liberalism; anti-racism has motivated people to come up with an updated version of 19th century race science, and 19th century scientism has popularized German mysticism—which, amusingly, still haunts the Enlightenment rationalists in their nightmares, especially since it seems to become popular again. Did I mention that dialectic is a bitch?

The way out of this dialectic circle, if there is one, can only be this: study history, think historically, ground yourself in history, realize that you are a product of history—as are your ideas, culture and society—and go from there. Get your hands dirty, do some historical research, and think hard about the meaning of it all.

Let’s give a little example as it relates to liberalism.

It’s the Reformation, Stupid!

We can talk about whether Hobbes’ state of nature was a schizoid fantasy or ground zero for our glorious liberal tradition; whether Bentham was a madman or a genius, Mill a proto-communist or the crowning jewel of the classical liberal tradition; whether Rawls’ veil of ignorance is another autistic spasm or the key towards unlocking a fair society; etc.

Or, we can leave the realm of timeless abstraction and look at how liberalism emerged in the first place. Put simply, the story goes something like this:5

Before the Reformation and the following disastrous religious wars, ruler, religion and people were one: the population was Christian, as was the Prince. Indeed, the ruler derived his authority from God. Any distinction between Christianity, ruler and people was meaningless, and therefore literally unthinkable. As was any notion of secular individual rights like “religious freedom.” Such concepts simply didn’t make any sense at all.

There were, of course, power struggles between pope and rulers, and a certain division of labor, so to speak, between worldly and religious authorities. But this division existed within the unified religious framework, the Catholic world view—even though people at the time couldn’t articulate it that way, for there was nothing to contrast it with, nothing to shine a light on and put a shape to their world. It just was.

Every time and place has their tenets which, to the degree people are even aware of them, they simply “hold to be self-evidently true.” Until something happens, that is, which challenges their assumptions and forces them to rethink them, revitalize them, change them, evolve them.

One major such occasion was the Reformation and the bloody wars of religion that followed in 16th century Europe. Suddenly, the situation looked very different: not only did you have neighboring Princedoms with different religions, but worse: after forced conversions, expulsions and religiociding your rival Christians eventually failed, you ended up with different places with different denominations within the same kingdom. Worse still, you even had cities divided between catholics and protestants.

In such an environment, the old internalized idea of unity between ruler, subject, and religion disappears with a loud bang—a bang that can perhaps be stubbornly ignored for a while by covering your ears, but whose resounding echo, whose tectonic gravity wave, will eventually get to you.

Imagine yourself living at such a time. No matter how much you hate the heretics or the papists, at some point, all you want is peace. Especially since the wars of religion were seen by many as deeply corrupting and perverting even the virtues of war. An anonymous author captured the mood in a poem published in Lyon in 1563:

Between father and son, mothers and daughters,

Between brothers and sisters, and nobler families,

The Sun has not seen such after fights,

Such extortions and such cruel debates.

For who tyrannized was most welcome,

And was exalted by the small people.

And the rascal, not having an apple in his hand

Is treated in broad daylight like a great gentleman.6

As French historian Olivier Christin explains, for this anonymous author, “the civil war does not appear to be the honorable and virile test in which the true valour of the well-born man will manifest itself. On the contrary, it leads to the very perversion of courage - which degenerates into ‘extortion’, ‘cruel debates’ and tyranny - and to the triumph of the parvenus, the impostors, the ‘rascals’, a judgment that can also be recognized in the disillusioned words of some of the active protagonists of the first religious war.”7

This also reveals something else: in a sense, it wasn’t liberalism that has done away with the knightly warrior ethos; rather it was the wars of religion which had so disillusioned people that they, in their existence at this particular time, were willing to give it up for the same reason they were eventually willing to create and accept powerful secular institutions. They wanted an end to the senseless, brutal, stupid, degrading spectacle.8

If you put yourself in the shoes of the king or prince, and your fury about the loss of the good old days of religious unity, of ruling over your subjects as God’s worldly representative, who by definition share the same religion and therefore accept your status, gives way to realism, you will be ready for compromise—and indeed, may use the opportunity to expand your power, with no regard for the long-term (in any event unpredictable) consequences.

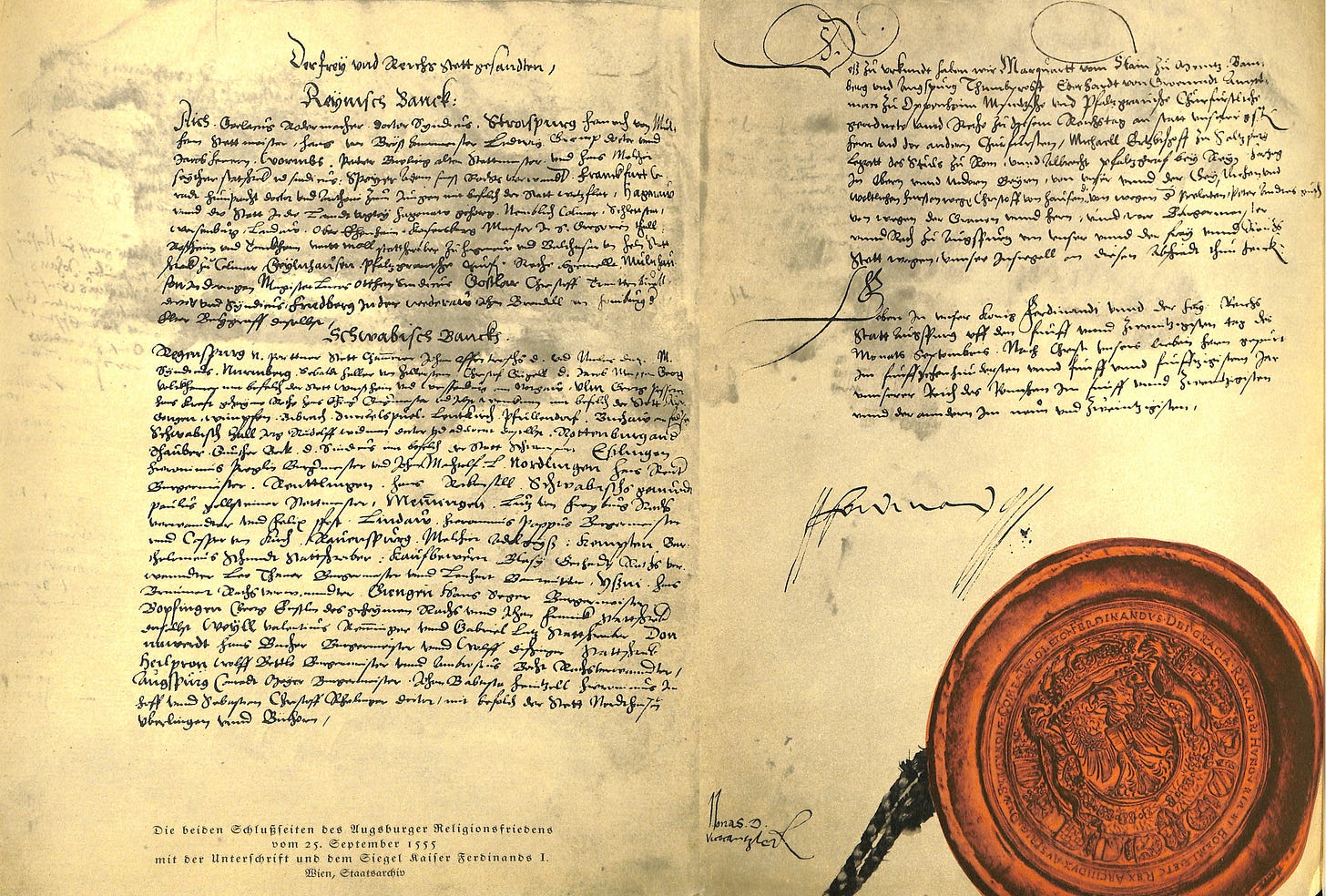

The solution to all of that were the religious peace treaties, notably the Peace of Augsburg (1555) in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, and the Edict of Amboise (1563) in France. A whole lot of issues concerning the relationship between catholics and protestants needed to be settled, and settled they were—badly.

To give an example of the enormous shift that a divided, pacified Christianity brought with it, and how the religious peace immediately began devouring the old unity of king, religion and people, consider this:

Without ceasing to see himself as a very Christian king and to benefit from the symbolic effects of the coronation ceremony, the King of France had to tolerate the Calvinist presence in the kingdom, in an apparently contradictory attitude that led Louis XIII, for example, to specify that the clause in the oath taken at the coronation committing him to eradicating heresy did not apply to his Protestant subjects. Would political belonging - being a subject of the King of France - correct religious belonging - being a Protestant? How can we fail to recall Michel de L'Hospital's famous 1562 statement to Parisian parliamentarians that "even an excummunié remains a citizen"?9

How indeed can a Christian ruler fight for his religion and against heresy if lots of his subjects are… heretics according to his religion?

We begin to see that it is precisely in the establishment of religious peace that we find the historical seed of secular liberalism, of the distinction between citizen and religion—of the modern state.10

Where there are different denominations living side by side, the religious authorities cease to be able to mediate, enforce, and decide when there are problems. Naturally, what you need is a more or less impartial referee, an authority independent of religion: you need what later would germinate into secular authorities. Of course, this idea wasn’t ripe at the time, the religious and worldly still more intertwined than we moderns can even imagine. But the very institution of the peace conferences and the compromises they developed can be seen as the first, crucial step towards establishing an “independent” authority, a secular regime—if only as a seed in the minds of those tasked with finding solutions.11

The schism created a schism in consciousness, too. What does it do to your mind when all of a sudden, there is another religion among your people that you need to live with?

A part of your mind moves beyond religion, splits off, so that it can look at both religions from a third place. Otherwise, your faith would tell you to fight the heretics or papists tooth and nail: to the religious mind, everything is at stake. But finding compromises, dealing with practical conflicts in daily life, naturally sets in motion a sort of dialectic that strengthens that supra-religious part of the mind, if only unconsciously. Eventually, while you still consider yourself fully Christian, fully catholic or protestant, a proto-secular consciousness comes into being; a new synthesis that lies beyond the old order of the mind that took the religious unity of life and its institutions for granted. With grave consequences.

Once the peace mechanisms were established, the monarchies had a new bureaucratic and rhetorical instrument at their disposal to cement and expand their authority. After the failure of the “dogma professionals” and theologians to reunite the church and end the conflict12, after the dream of a universal creed was over, came the hour of the worldly bureaucrats, the politicians, lawyers, technocrats and central planners: thus was born the State.

Edicts, declarations and ordinances on the subject of peace regularly and firmly insist on the absolute necessity of re-establishing royal authority, everywhere and over everyone, while asserting that they will not intervene in doctrinal matters or force people's consciences.13

Non-interference in doctrinal matters while expanding central power: the runaway train was set in motion. On all levels, and especially on the local city levels, the authorities established a secular “juridification,” a technocratization of society in the name of protecting doctrinal independence and individual choices.14

In this way, the Peace forced denominational parties, nobles, local authorities and ministers to convert some of their militant strategies to precise, technical and rigorous forms of legal confrontation. In this sense, we can indeed speak of a Verrechtlichung [Juridification], a moment of innovation and intense legal reflection, in the wake of the peace of religion, to which not only the theoretical works published at the time bear witness, but also the day-to-day political practice of denominational parties and authorities.15

One of the bones of contention was the right to choose one’s religion, the Freistellung. It wasn’t comparable to what we understand under freedom of religion, but it can be seen as a sort of proto-individual right. Out of this mélange of securing peace via compromise, supra-religious institutions and individual rights rose our fancy liberal theories.

But these things weren’t established because of some groundbreaking philosophy. They came to be as an answer to a specific historical question: how can we find a compromise between catholics and protestants, between neighboring cities and neighborhoods within cities—so that first the bloodshed, then the administrative conflicts, can be resolved? It was not that people wanted that sort of thing. Rather, it emerged out of this multidimensional situation and the attempts of various factions to solve it while guarding their interests.

After this groundwork had been laid, later, philosophers would come unto the scene and work from there, creating elaborate theories that justified and expanded upon the order they found themselves in, using this tradition to grapple with the challenges of their own time. Seeing how secular institutions and individual rights guaranteed by these institutions have helped Europe get out of the chaos, indeed how they coincided with progress and innovation, they doubled down on these core ideas, developed them further, adapted them, and helped make them part of the Western core identity. But not without its downsides and built-in time bombs.

This is a good place for a paywall.

But I don’t like paywalls, and I know you don’t either. Keep in mind, however, that I spend a lot of time researching and thinking about what I write here.

So, to help me keep my work free and support my efforts, if you’re feeling it, do the right thing and upgrade to a paid subscription—you can of course cancel it anytime:

What It Means for Today

Once we know about liberalism’s roots in the pacification process after the wars of religion in the 16th century, some of its inherent problems and limitations become clearer.

It is rather obvious, for example, that liberalism can’t deal well with the immigration and integration of large numbers of foreigners who have an entirely different background religiously, culturally, and ethnically. No wonder, given that it emerged in the context of a conflict between people who, despite their doctrinal differences, were all Christians rooted in more or less the same culture and homeland. At some point, our inherited mechanisms of conflict resolution break down when the “shared cultural capital,” the deeply held foundational beliefs, fracture. Hence we don’t know what to do about Burkas, about abortion, about religious freedom, freedom of speech, and so on. Liberalism was never meant to answer those questions, because they are our questions in our context.

Here’s another example.16 After the religious peace was official in the 16th century, all kinds of conflicts erupted. One of them concerned official holidays: in a divided city, would the protestant shop owners have to close their shops on a catholic holiday, and indeed decorate their shops when the processions marched through the city? Obviously, some kind of resolution had to be found. You can see how the liberal logic played itself out much later based on a very specific historical conflict: finding a compromise between catholics and protestants is one thing, but what do you do when you have atheists, Muslims, Jews, Greek orthodox, etc. in your town? Why shouldn’t shop owners decorate their shops however they want and open whenever they want? Wasn’t the whole compromise about “freedom of conscience?” Naturally, what you end up with eventually is the abolishment of all official holidays. While we are not quite there yet, today, you can go shopping on a Sunday, Christmas decorations—especially Christian symbols—are on the way out, and the only reason why holidays still exist at all is because people like them, and so they keep them, barely, in a more and more secularized form.

Another way of putting it is this: liberalism, as it developed from the times of religious peace, is founded on the division of consciousness mentioned above—a division that created a supra-religious part in the mind, in other words, carved out a secular space in the collective soul. Hence its inner logic will make it gravitate towards an unreligious, even atheist stance. It’s just that this is less obvious as long as it only has to deal with catholics and protestants.

Today, we don’t just see fundamental fractures between native Western populations and immigrants, but also along political-religious lines—to the point that in the US people talk about secession in all seriousness. Perhaps we can draw a parallel here to the 16th century. How to solve the issue? The answer back then was first all-out war, then a fundamental change in the nature of authority and how people related to it. It was to create and strengthen bureaucratic institutions and mechanisms of conflict resolution, from the big questions down to everyday quarrels about cemeteries, church allocation, public services, and so on. Some people today might be tempted to similarly create new “impartial” institutions, or change our understanding of authority, if this can help to secure peace. Or one might opt for secession, but as the Reformation shows, this may not only involve lots of bloodshed, but turn out to be impossible: you may still end up with that papist bastard, or that satanic heretic, as your neighbor.

As for the second camp, the RETVRN-style neo-reactionaries, it's a bit too easy for them to blame liberalism for our modern woes, and to see in liberal theories and the Enlightenment the seed of our religio-cultural downfall. The fact is, those who laid liberalism’s foundation were not “rationalist” anti-Christians, or heralds of the Faustian age, or Prometheus figures playing God, or subversive slave moralists worming their way into the God-given hierarchy. They were Christians dealing with the—to their minds—utterly tragic loss of Christian unity and the resulting killing spree, cruelty, and dissolution of society. They had no choice but to come up with solutions to the untenable status quo, and they could not have foreseen that by doing so, they would create secularism, technocracy, liberalism and, as those in the second camp would have it, our own godless society that is so detached from any deeper sense of Reality that it has adopted the most hideous and stupid ideologies as ersatz religions.

Similarly, you might criticize and blame Rousseau and Mill, Kant and Hume, Hegel and Russell, Carnap and Steiner, Adorno and Popper all you want, depending on your political leanings and understanding of history—they all got things wrong, but they all tried to answer questions that their historical moment posed in their own limited ways. To claim that Rousseau could have had any understanding whatsoever of “wokeness” would be as absurd as claiming that Hume created 19th century scientism, that Kant is responsible for postmodern relativism, or that John Stuart Mill led to third wave feminism.

Studying history means swallowing a most bitter black pill: the realization that, thanks to what I’ve called “unholy dialectic,” no matter how good the intentions or how wise the outlook, every solution people have found eventually seems to be used as a weapon to turn everything to crap—again. Which also means that whatever our solutions are, they will also backfire eventually. Unless, perhaps, we manage to take a broader view, recognize these things by thinking historically, and manage to solve our problems in a more nimble, better informed way.

Think historically. Think in terms of organic processes, of dialectics, of interconnectedness, of people thinking and acting based on those thinking and acting before them, of more or less bright folks, more or less deceived by their own limits, grappling with the specific issues of their time.

Proper respect for tradition is not about holding something to be timeless, but rather about recognizing that we are beings in time: historical beings. Wise traditionalists don't preach abstract-timeless ideologies from the past; rather, they recognize deep roots worth studying.

We are all creatures of history; as much as we like to pretend that we, as opposed to all those other ignoramuses in the past, have figured out universal truth and can take the bird's-eye view, we can’t. Our minds are shaped by history; we can’t help but think along lines that are congruent with the overall mind shape of our historical and civilizational moment.

Does all that mean I completely deny that there is such a thing as universal reason, universal truth, or better or worse ideologies? Of course not. As I have put it elsewhere, saying anything at all means lying by omission. There are always other angles from which to look at things. What mitigates this conundrum is that utterances don’t exist in a vacuum: they, too, must be seen in context. Which today is that we are immersed in autistic abstractionism, amplified by the Sperg Brigade being attracted to online discourse like moths to the light, and that historical reasoning, as I understand it here, is often criminally neglected. That’s why I keep hammering home that point, and why I lately engage in these little historical inquiries.

Whether you prefer going back to “classical liberalism” or reject it, you must first understand it. Reading the philosophical classics is just part of it, because these works have a history, a context, behind them. Only by looking at it that way can we grasp the strengths and weaknesses of such ideas as they play out over time.

I don’t know about you, but I find these sorts of insights deeply—and strangely—liberating. Granted, we may be talking about just another little piece of the puzzle here. But it’s as if something that bothers you in the back of your mind for your whole life without you even knowing it suddenly disappears, and you can breathe freely for the first time.

Something to strive for.

I was planning to write something about liberalism and the wars of religion for a while, but what prompted me to write this up was

’s piece Four Big Questions for the Counter-RevolutionThis was one of R.G. Collingwood’s deep and productive insights, as outlines in his Autobiography and Essay on Metaphyiscs.

Religious people might claim that while they agree with me in general, their religion is exempt from this sort of historical reasoning, that it is indeed timeless and universal, containing within it and transcending all history, perhaps as a sort of meta-truth or meta-history. That’s a debate for another day.

R.G. Collingwood spoke of and traced what he called “encapsulation:” the fact that even if a culture and its ways of doing things entirely disappear, such as after centuries of occupation, it can retain a certain subtle spirit, a seed that is passed on from generation to generation, which can again germinate and recreate elements of the lost culture.

For a very insightful inquiry into how the 16th century shaped the modern idea of the state, see

Olivier Christin, La Paix de religion : L'autonomisation de la raison politique au XVIe siècle, Seuil, 1997

Translations of the following referenced parts mine.

Original French, quoted from Christin, p. 27:

Entre le père et le fils, entre mères et filles,

Entre frères et soers, et plus nobles famillles,

Le Soleil n’a point veu de si âpres combats,

Telles extorsions et tels cruels débats.

Car qui tirannisoit estoit le mieux venu,

Et estoit exalté par le people menu.

Et le coquin n’aiant vaillant une pomme

Estoit prins à plein jour comme un grand gentihomme.

Christin, p. 27

There had been precursors to this development. The peace of 1495 (Ewiger Landfriede) saw the establishment of imperial courts in Germany, whose task it was to implement the peace, part of which was an abolishment of feuds and the settling of issues among noblemen through legal means.

French original (Christin, ch. II):

Sans cesser de se donner pour roi très-chrétien et de bénéficier des effets symboliques de la cérémonie du sacre, le roi de France doit bien se résoudre à tolérer la présence calviniste dans le royaume, dans une attitude apparemment contradictoire qui conduit, par exemple, Louis XIII à préciser que la clause du serment prononcé lors du sacre l'engageant à extirper l'hérésie ne s'applique pas à ses sujets protestants, L'appartenance politique — être sujet du roi de France - corrigerait-elle l'appartenance religieuse — être protestant? Comment ne pas songer ici à la formule célèbre de Michel de L'Hospital affirmant en 1562 devant des parlementaires parisiens que même l'excummunié ne laisse as d'être citoyen»

Carl Schmitt, writing in 1956, saw the importance of the wars of religion for the genesis of the modern state as well, as he wrote about in Hamlet oder Hekuba; see Christin, p. 12

There were people both among protestants and catholics at the time who intuitively saw the writing on the wall, and opposed the religious peace on the ground that religion is the “social link and political cement” — see Christin, p. 59

Ibid., p. 34

Ibid., p. 38

“…the divergence of the vocabulary between the theologians-humanists-literati on the one hand, and the jurists-officers-politicians on the other, forms a constant…” — Christin, p. 40

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 111

While I understand the impulse behind the RETVRN movement, I think your post lays out the fundamental flaw. We cannot return to something we don’t even truly understand. Return to the traditional Christianity of centuries ago? Our minds wouldn’t grasp it as they did, our civic sensibilities wouldn’t allow for it.

Inspired piece of writing. Thank you